-

Published: 27 March 2023

Nanotechnology is a rapidly advancing and truly multidisciplinary field involving subjects such as physics, chemistry, engineering, electronics, and biology. Its aim is to advance science at the atomic and molecular levels in order to make materials and devices with novel and enhanced properties.

Edited by |Chrisitan Megan

Science section

26 March 2023- this study is copied from a paper published in 2007

The potential applications are exceptionally diverse and beneficial, ranging from self-cleaning windows and clothes to ropes to tether satellites to the earth’s surface, to new medicines” [1]. Some, however, have claimed that nanotechnology might lead to nano assemblers and potentially self-replicating nanomachines swamping life on earth. This so-called ‘grey goo’ scenario was first described by Drexler in his book Engines of Creation [2], a scenario he now thinks unlikely (as of 11 June 2004), but which has been integrated into fictional narratives such as Michael Crichton’s novel Prey [3], has provoked comments by the Prince of Wales, lead to inquiries by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering in the UK, and, in general, taps into wide-spread fears about loss of control over technologies [4, 5]. Another popular image of nanotechnology, the view that it will lead to tiny robotic submarines traveling through the human bloodstream and repairing or healing our bodies is equally ubiquitous.

Nanoscience and Technology

However, there is, as Richard Jones pointed out in a recent article on “The Future of Nanotechnology”, an almost surreal gap between what the technology is believed to promise (or threatens to create) and what it actually delivers [4] – a gap that certain science fiction scenarios can easily fill, be they of the dystopian, grey goo type, or the utopian, spectacular voyage, type. This view was echoed by López in his 2004 article “Bridging the Gaps: Science fiction in nanotechnology”, in which he explores how nanoscientists themselves have employed devices from sci-fi literature to argue the case for nanoscience. He comes to the conclusion that “the relation between SF narrative elements and NST [nanoscience and technology] is not external but internal. This is due to NST’s radical future orientation, which opens up a gap between what is technoscientifically possible today and its inflated promises for the future.” [6].

Vehicular utopias [7], from Jules Verne’s Nautilus voyaging under the sea to nanomachines navigating through our bloodstreams, have, for a long time, filled this surreal gap between the technologically possible and the technologically real and can have an immediate and long-lasting hold on the public imagination. They continuously serve to science fictionalize science facts and blur the boundaries between cultural visions and scientific reality [8,9].

Nanosubmarines

This paper examines the visual and verbal imagery surrounding the various ‘submarines’ that have traveled through popular imagination from Verne’s Nautilus, driven by Captain Nemo, up to the more recent representations of nano-submersibles, some of their facts, some of them fiction and many more floating between the two. It retraces the voyages of iconic submarines from the 1870s, when Verne wrote Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, up to the present, from the journey through the hidden space of the world’s oceans on board the hidden space of a luxurious submarine, to expeditions into the hidden space of the human body and beyond to outer space.

Popular Culture and Nanoscience

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that popular culture and imagination do not simply follow and reflect science. Rather, they are a critical part of the process of developing science and technology; they can inspire or, indeed, discourage researchers to turn what is thinkable into new technologies and they can frame the ways in which the ‘public’ react to scientific innovations. Popular culture talks about space rockets before there are space rockets, test-tube babies before there are test-tube babies, and clones before there are clones. Before scientists do anything there is often a ready-made public perception of how good or how bad it is going to be, derived from this social, literary, and cultural precognition. So when science does these things for real, their image has already been formed - for good or ill. Fictional images, be they lithograph in 19th-century children’s books, stills from popular sci-fi films, or nano-illustrations produced by professional science illustrators play an important part in this process. It might be going too far to say that science can only discover what has already been created in imagination, but it is certainly the case that science can only flourish in society when popular imagination does not strongly oppose its development. This might be why some nanoscientists have also become nano-visionaries, actively involved in creating an imaginative and imaginary space for nanoscience in modern society through writing and illustrations.

In the following I shall first summarise some insights into the way science and fiction interact inside nanoscience, then provide an overview of the iconographical voyage of progress accomplished in and by the Nautilus, to be followed by a section in which the Nautilus meets other science fiction influences and merges with nanoscience proper, only to be taken, finally, from the inside of the human body into outer space. I shall then try to draw some conclusions from this voyage through visual space and time.

Monoculture and Nanowriting

A recently published book entitled Nanoculture: Implications of the new technoscience begins with the sentence “Imagine a world …” [10] and goes on to describe a world, our world, in which nanoscience and nonfiction have begun to interpenetrate each other in myriad ways and where the boundaries between the literal and the metaphorical and the real and the imaginary have become utterly blurred.

Nanobots, Nanomachines and Science Fiction

There is one discursive knot in what the contributors to the book called ‘nano-writing’ where this blurring becomes most obvious: the so-called nanobot. Nanobots have long been the stuff of science fiction and they have, more recently, become the stuff of science-fictionalization when some nanoscientists talk about these not-yet-existing but soon-to-exist nanomachines as if they were as real as the metaphorical motors, machines or pumps that float through our body in the shape of enzymes or parts of bacteria. As one nano-writer points out in an article entitled “Of silicone and submarines”: “After all, the most successful nanomachines ever created are those operating inside every cell”. [11] Hence, writes Bensaude-Vincent, “the debate about the potentialities of nanotechnology basically boils down to the question ‘what is a nanomachine?’ However, the notion of the machine is itself polysemic, so that it can support dissimilar views of living systems and teach quite different lessons to nanoscientists and engineers” [12; see 13]. It can also support dissimilar images of the future and teach quite different lessons to the scientifically interested public. The nanomachine I am interested in in this article is the nano submersible, which has mainly positive associations, unlike the nano-assembler which replicates and destroys the earth. These two visions of a utopian or dystopian nano-future seem to match the different discourses of hope and fear associated with either medical GMOs (genetically modified organisms), which are regarded as rather beneficial, and environmental GMOs, i.e. foods and crops, which are not [14].

The Various Guises of Nanobots

Nanomachines, in the shape of nanobots, flip not only between the corporeal and the mechanical, the metaphorical and the literal and the fictional and the factional in an almost quantum-mechanical way, they also flip between good and evil, the past and the present and the present and the future. They can invade or heal the body, destroy the world or make it a better place. They are part of a future that will, as many nano writers say, inevitably become the present and they have been part of our past imagination for many years. One incarnation of the nanobot in particular, the nano-submarine or, as one can call it, nanobot, has, as we will see, a long and illustrious fictional and visual ancestry, which links the future to the past, woodcuts to computer-generated images and lithographs to nanolithography [15].

The motor of metaphorical imagination which powers fictional imagination, be it verbal or visual, namely seeing something as something else, is all-important in the process of flipping between body and machine, fact and fiction, past and future, hope and fear. Machines are seen as biological phenomena, biological phenomena, including human bodies, are seen as machines, small objects are seen as large objects and large objects are seen as small ones, the outside is seen in terms of the inside and the inside in terms of the outside, science is seen in terms of fiction and fiction in terms of science. This reciprocal metaphorisation of the real and the not-yet real in nano writing is quite unlike traditional uses of metaphor and imagery in science and of science in fiction where scientists use metaphors or metaphorical models to describe as yet unknown aspects of the real world and where science fiction writers use science as a starting point beyond which to project imaginary scenarios – from the known to the unknown and from the esoteric world of the lab to the lay world of ordinary discourse. By contrast:

The blurring of potentiality and actuality in the nanoworld, and the lack of general knowledge about nanotechnology, create a fertile imaginary around the new discipline. A common nightmare speculates that, with the aid of nanotechnology, researchers will build nanostructures capable of replicating themselves like nano-robots. UCLA Professor James Gimzewski relates that when he worked at IBM “a newspaper called the Bild printed a front-page story saying ‘IBM creates nanobots that can cure cancer’ with pictures of them swimming inside the human body and describing it as having a cancer-killing unit that used lasers to ‘blast away’ the cancer cells.” Immediately, there were people from all over the world calling IBM and asking how to get these nano-bots. [16]

Nanoboats Break Down Barriers between Fiction and Reality

This story was not true (at the time) but it is indicative of how iconic and at the same time real nanobots have become in the public imagination, in this case, reproduced in the shape of a tabloid picture and nano-hyperbole [17]. Nano-writing, be it in scientific magazines, in novels, or in tabloids, “removes”, as Milburn points out “all intellectual boundaries between organism and technology” and “causes ‘the distinction between hardware and life… to blur’ – and human bodies become posthuman cyborgs, inextricably entwined, interpenetrant, and merged with the mechanical nanodevices already inside of them.” [8] The imaginary, not yet real, nanobot swimming inside our body is conceptualized as if it were already real, as ‘real’ as the biological ‘machines’ swimming inside our body on which the nanobot is modeled.

Nanotechnology in Children’s Culture

Whereas some parts of public/adult imagination about nanotechnology have been nurtured by the tabloids and by popular novels (where nano has been portrayed mostly in dystopian ways), children’s nano-imagination has been nurtured by cartoons, comics, novels, and computer games, in which nano has perhaps not only negative associations (but more research is needed here). What links the two, adult and children’s imagination, are images are taken from children’s literature and films, such as Verne’s novel and its Disney film adaptation Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, which were then transferred to adult films, such as Fantastic Voyage and Inner Space and transferred back again to children’s media, such as Dr. Who and Invader Zim (see table 1), with the (nano)submersible weaving forwards and backward between media and audiences. This process of interpenetration also involves a give and take between ‘éducation et récreation’ (the motto under which Verne’s novels were published in the 19th century), between fact and fiction, and between rationality and imagination. This seems to contradict Peter Weingart’s claim that “[s]ociety obviously does not consider science a matter of amusement” [18]. When it comes to nanobot (a)ts it certainly does.

Modern children’s fiction refers to nanoscale creatures and machines so frequently that flippant remarks about ‘nano’ have become permissible. In a recently shown episode of the Disney cartoon, Kim Possible one character points to something and calls it ‘nano’. The other character asks what that means and is told: “Small, mini, tiny, minute.” Asked why he then didn’t say ‘mini’, he replies: “because nano sounds a thousand times better, why else?” In short: Nano is cool.

Reality is Catching up to Science Fiction

But just as language, especially teenage slang and ‘teenage’ technology in the form of the iPod Nano, is catching up with imaginary nanobot (a)ts, reality may be catching up with them, too. In a recent article about nanoscience (chosen amongst many), we are told about a new Institute at Leeds University dealing with nanotechnology:

Molecular-scale ‘trains’ and ‘submarines’ that will carry loads such as tiny doses of drugs and virtual reality software to enable operators to control matter on the nanoscale are projects planned by the Institute.

Professor Peter Stockley […] said: “[…] In the future, we could imagine an engineered ‘nano-submarine’ swimming around a patient’s bloodstream to the site of a tumor too small to be tackled by surgery.” [19]

Nanosubmarines in The Press

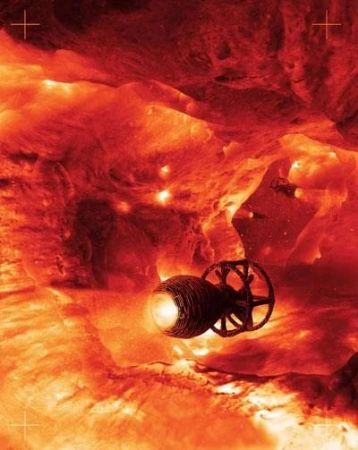

In the year 2000, an image of a tiny robotic submarine traveling through a human artery traveled round the world and was even pictured in the UK tabloid newspaper The Mirror (Thursday, 7 September 2000) under the title “Fantastic Voyage 2”. This tiny 4mm long craft was said to be able to save lives before the end of the decade, to be able to cruise through blood vessels using sensors to check for signs of illness and cancer and, it was reported, may one day be able to repair arteries and hearts. It was there to demonstrate in a visible way what could already be achieved in the field of micro- or nanotechnology. A similar picture was also exhibited at the Hannover Expo 2000 [see 11].

The year 2000 image of a prototype of a nano-submarine, which circulated widely in the press, appeared a century after a picture of Jules Verne’s Nautilus had graced the visitors’ guide to the Paris Expo in 1900 [20], a sign that the Nautilus had become part of modern mythology (see figure 1 for another example). We seem to have come a long way in a century, but we can’t seem to leave the Nautilus myth quite behind us yet – and, as we shall see, it would soon merge with the nano-myth. (It should be stressed however that the year 2000 image was not the first. An image of a nano submarine swimming through a capillary and attacking a fat deposit, such as normally may accompany an arteriosclerotic lesion, was published as early as 1988 in an article for the Scientific American, for example [21]).

Nanoboats in Defence Applications

Moving away from nano-medicine, the year 2003 brought news that ‘nano-fish-boats’ could be invented to spy on (real/real-size) submarines:

The concept of “nano under the sea” is not so far-fetched. The move to Advanced SEAL Delivery System (ASDS) minisubs, to torpedo-tube-launched unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) for minefield surveillance and other dangerous duty, and the planned armed unmanned undersea combat vehicle MANTA, can be viewed collectively as a trend toward miniaturization serving twin purposes: increasing stealth, and minimizing casualties if stealth were compromised. [22]

Before these various medical or military futures catch up with the present, I would like to look at the past and explore the genealogy and iconography of imaginary nano-bo(a)ts, especially nano-submarines, that have nurtured popular imagination and might still be nurturing the imagination of artists who produce nano-illustrations deposited at the ‘Science Photo Library’, for example, from which some of the illustrations for this article have been taken. Such images, which draw on both technical and aesthetic expertise, depict the progress of nanoscience while at the same time driving it forward.

An Iconography of The Nano-Boat: From Nemo to Nano

As shown in previous studies [23, 24, 25, 8] popular culture and imagination do not simply follow and reflect science; rather, they lead and anticipate developments in science and technology. This is nowhere more apparent than in nanoscience, especially as far as the nanobot is concerned. Let us now look more closely at the way it has traveled between popular and scientific and adult and juvenile imagination.

Evolution of the Nano-Submarine

The following (rather incomplete) table charts the origins and development of the nano-submarine that has enchanted readers and viewers for more than a century and a half

{source}<script async src="https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js?client=ca-pub-4474625449481215"

crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

<!-- moss test ad -->

<ins class="adsbygoogle"

style="display:block"

data-ad-client="ca-pub-4474625449481215"

data-ad-slot="6499882985"

data-ad-format="auto"

data-full-width-responsive="true"></ins>

<script>

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

</script>{/source}